Farming: It’s Not a Job, It’s a Way of Life

Part 2 - Kevin’s Journey

September /October 2025 - edition 11

In case you missed Robin’s edition, the title for this is a quote from This Farming Life, an amazing BBC documentary series that follows the lives of farming families in Scotland, Northern Ireland and the north of England. Robin took us through her personal journey and now Kevin takes the wheel. And oh, what a journey it’s been! Enjoy the ride!

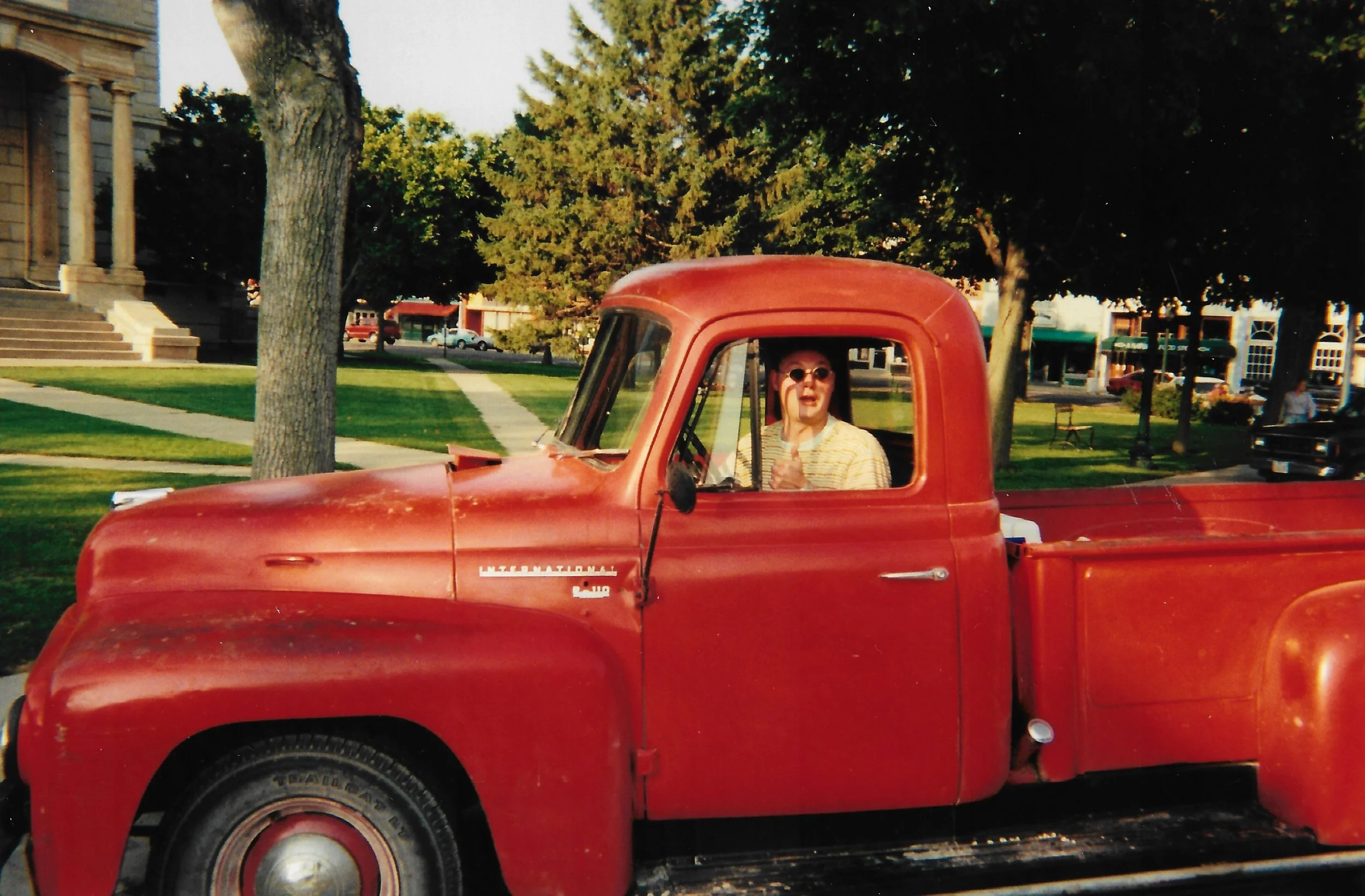

A symbol of Kevin’s farming journey - the 1955 International R-110 that now resides at Branchwater

“Ol’ 55,” Closing Time, Tom Waits, 1973

If you’ve ever been to Branchwater, you will have noticed the 1955 International R-110 red pick-up truck parked at the east side of the grain field by the barn, north of the feed bins. She has seen better days, but she’s also seen worse. The truck currently has a hole in the gas tank, and it’s been difficult to find a replacement tank to get her on the road again. She’s temporarily stopped, but she’s logged a few miles in her day.

I don’t know when my grandparents bought the Binder, but it was used when they got it, and I believe it was when my mom was in college, so the truck would have been ten to fifteen years old when it came to my grandparent’s Iowa farm. It was nicknamed “Ole Smokey” for its expressive exhaust output, and it served as a typical farm truck for them: hauling bales of hay and straw, dragging out timber, moving small equipment from field to field.

When we were kids visiting our grandparents’ farm, the truck sat idle, but we’d sit inside the cab and pretend to drive it, chasing bank robbers, racing through the streets—or engrossed in whatever make-believe we were acting out, shifting the gears without engaging the clutch, as the truck sat motionless in the Quonset near the barn. That barn was torn down when I was in college, and the Quonset has also been gone for several decades now too. Our grandparents’ farm has long been sold, but that International R-110 is still here. That’s the very car in which I learned to drive. My older cousin, Brad Johnson—who spent more time at our grandparents’ farm than we Pike kids did—taught me to drive on it one summer when I was twelve or thirteen, I don’t remember for sure.

Brad explained what a flywheel was and how engaging the clutch kept the engine connected to the transmission while it wasn’t in gear. He taught me how to start in second, since the R-110 had a hauling gear in first, which was too low for road use. He taught me how to slip the clutch and to downshift. The steering was so sloppy in the truck that when you hit a slight bump in the road at 40 miles per hour, the steering wheel could turn to 10 o’clock or 2 o’clock on its own, but the truck would continue straight down the lane. The R-110 smelled of mice and gasoline, and I fell in love with that truck.

Grandpa Johnson transitioned from farming to insurance as far back as I can remember him. He entered into an agreement with his cousin, Clifford, whereby they split the cost of the soy bean and corn seed, my grandparents provided the land, and Clifford the labor; and they split the profits come harvest. But State Farm Insurance was grandpa’s main source of income since the 1970s. By the time I had my driver’s license, grandpa only insured the R-110 when he knew I was coming to Iowa for a visit. He’d also have to recharge the battery and give her a few blasts of starter fluid straight into the carburetor to be sure she would fire when I was there.

Binder with boy Kevin (front), cousin Phil, and Grandpa Harold

“Come On Up To The House,” Orphans, Tom Waits, 2006

I was a typical Midwestern boy, though I always thought of myself as more urban. Columbus, Ohio was certainly more sophisticated than Akron, Iowa, after all. The suburbs held far more adventure than acres of corn; Wendy’s oddly squared cheeseburger patties were surely better than Dean’s Dugout smash burgers, where you could sit on sticky picnic tables and have a view of the grain Co-op’s soaring concrete silos across the railroad tracks and Highway 12. Yet, whenever I was back in Iowa in my teenage years, I spent hours in Ole Smokey, driving down the gravel roads outlining the sections (a section is one square mile, or 640 acres) practicing how to start a stick shift on a hill, or deliberately peeling out, shooting gravel far behind me. One summer after our parents died, my brothers and I tore down a decrepit corn crib and loaded the old timber in the back of the pick-up to haul it away. I learned how to change the oil and replace the water pump on the pick-up, and I used to keep a .22 rifle in the cab, and I would drive to abandoned corn bins and straw sheds to take aim at the rodents. There were no seatbelts in the R-110 (there still aren’t), and driving recklessly in the middle of field felt carefree and wild to my suburban, teenage self.

In retrospect, I realize now that what I was witnessing was the demise of the Midwestern family farm. My grandparents had transitioned from a multi-use farm with animals and various crops when my mom was a girl, to cutting out all sentinel trees to increase crop acreage and abandoning animals in favor of corn and soybeans. Ultimately, my grandfather left the day-to-day farm business altogether when he changed careers to selling State Farm Insurance. Clifford kept a small herd of cows there, but after he retired, my grandparents leased the farm to another farmer, Blaine, who also managed several thousand acres of corn and soybeans to make a living. The 340 acres my grandparents originally farmed was too small to support a family in latter part of the Twentieth Century.

When I graduated from college, my grandparents flew to Philadelphia to come to the commencement. Afterwards, I took them to see Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, and since my grandparents were into antiques—and my grandfather was an avid clock collector—I drove them to Douglessville, PA to visit Merritt’s, where my grandfather purchased clock parts for repairs. Grandma Helen collected trivets, and she had hundreds of them. The logo of the tree in our branding is a copy of the Tree of Life trivet which came from her collection. We visited Longwood Gardens, and toured the Brandywine River Valley. We made our way from the seat of American Independence through the steel mills of Pittsburgh, across I-70 through Columbus, Indianapolis, north to I-80 and west to the Quad Cities, Des Moines on the endlessly straight and flat interstate to Sioux City, then—not to cross into South Dakota—north to Akron and the farm. We talked about farming along the way. Grandpa Harold experimented with terraced crop fields in his deep loess hills along the South Dakota border, and published his findings with the USDA. He was a full Swede. His mom, Elsa, came to America in 1905 and his father, Carl Johan Johanson, came around the same time. Like many Swedes, they came to Iowa, the Dakotas and Minnesota. Grandma Helen’s grandfather was a Ross, from Germany, who came to America as a stowaway on a freighter. They’d likely all be considered illegal immigrants today, certainly the stowaway, Frederik Ross would. We also talked politics along the drive, which we didn’t really agree on, and we talked about values and clocks, which we did.

After a few weeks at the Iowa farmhouse, my grandpa told me that I could have the R-110 as a graduation present.

Kevin’s graduation from Swarthmore with Grandparents Harold and Helen Johnson, Grandma Betty Jane Pike and brothers Paul and Scott

The day Stephan Blatti and Kevin left for their journey from the farm in Iowa to Ohio

“Sins Of My Father,” Real Gone, Tom Waits, 2004

It took a few years to get back to Iowa to collect the pick-up, but one summer, my best friend, Stephan Blatti, and I flew from Columbus to Sioux City and started our trip back to Ohio. The Binder has a top speed of 55 MPH, but she feels unsafe at any speed, which meant we had to take all back roads. We set out one morning with Tom Waits’ “Ol’ 55” blasting from a boom box that Stephan had wedged between the floorboard and the hand brake. These were the days when mixed tapes moved to CDs, and Stephan had recorded several of them for our journey. Little did we know that the ride would be so bumpy that the disc would skip incessantly, so we were without music for the 900 miles to go. What had been planned as a three-day trip ended up taking us nearly two weeks. We first had to cross into South Dakota to go south to catch a state highway that would bring us back eastward. We broke down the first time not even 90 minutes into our journey. That was a quick fix, and we were back at it, only to break down west of Davenport, Iowa, where we holed up at a strip motel. We spent our time at the Dusty Rose Restaurant & Lounge playing pool, throwing darts and drinking beer for the better part of four days as we waited for parts to arrive. We drove through some of the bridges in Madison County and on through Nauvoo, Illinois where we were treated to a private tour of the jail where Joseph Smith was shot, because we couldn’t wait around for the next timed tour. Then, we picked-up State Highway 36 through Indiana to Highway 40 into Springfield, Ohio and back to Columbus.

The Binder was not at home in German Village, where I lived in Columbus, though I did take her out now and again. After my grandfather passed, my grandma came to visit me in Ohio, and I drove her back to the airport in Ole Smokey when she departed. Poor thing, she probably had to smell the exhaust all the way back to Iowa. And, in the winter of 2000, I slipped on a patch of ice and totaled my normal car, so I drove the R-110 for the remaining few months I had left in Columbus before I moved to Harlem to take the job of Director of National Sales and Marketing at Skurnik Wines. When I left Columbus for Manhattan, I knew I couldn’t take the pick-up with me, so I stored her in the parking lot of an old lobster processing warehouse turned wine distribution facility that a friend of mine ran his wine company out of. He lost his lease, didn’t tell me, and the Binder was repossessed as abandoned by the landlord as payment for the lost lease. I had to fight to get her back, and I ultimately paid several thousand dollars to regain the title. Afterwards, I moved the Binder to a mechanic for a complete restoration. And this brings us to Branchwater.

I was assured that the restoration was completed in 2012, and so I made plans to go back to Columbus the following summer to drive the pick-up in the Upper Arlington Fourth of July Parade, where July 4th is taken extremely seriously. Moreover, I was in love with Robin. I had already relocated from Long Island, where I raised backyard chickens, to my neighbors’ chagrin, to a rental house in Staatsburg, and I had been looking for a farm since arriving in the mid-Hudson Valley.

Why? I was frustrated with my job and couldn’t find any opportunity for growth; I was divorced with two little kids; I had spent nearly twenty years in the wine business selling products made by others, and I longed to make something myself; I craved working with my hands and a more physical job; and, undoubtedly, I romanticized my own childhood and the time I had spent on my grandparents’ farm, and—certainly because of the divorce—I wanted to try to create that feeling for my children.

But I had fallen in love with a woman who was named after a bird. She was someone who had to stay in state for college, where she studied Art History at the University of Virginia, and then fled to Portland, Oregon upon graduation, a bird out of the cage. After a few years, she was off again to Italy. Verona, and a different life in the village of Romeo and Juliette. She worked in international development and traveled frequently to China and Africa. Travel is part of her identity. But she left Italy in a migration back to Virginia, then north to New York in the fall. And maybe she came to New York for some of the same reasons I did—to start again.

“New Coat of Paint,” The Heart of Saturday Night, Tom Waits, 1974

It was early in our relationship, and we were negotiating the separation between New York City life, where Robin still predominantly resided, and the Hudson Valley where I was renting a house and looking for a farm. But while driving down Salisbury Turnpike in spring 2013 to get a street-eye view of an old Stagecoach property up for sale, I saw—on the south side of the road—what would become Branchwater, also up for sale. I set up a visit the same week. It was just me and the realtor in a house that hadn’t really been touched up in three generations. The property listing was titled “Grandma’s Farmhouse.”

Then I had the idea that the International R-110—stored at a former Lobster processing warehouse turned wine distribution hub, seemingly “abandoned,” re-possessed, litigated, re-titled and ultimately restored—should be on this farm, and so should I, and so should a family.

I pitched the idea to Robin to fly back to Columbus with me to see where I grew up, collect the R-110, drive it in the Upper Arlington Fourth of July Parade, and then to just chase the sunrise east to the Hudson Valley, along only back roads, of course. She accepted, and so we flew to Columbus for what was planned to be a week’s getaway.

That’s all Robin knew. What I had also planned was to cross the Hudson at Nyak, then make our way up from Tarrytown to Sleepy Hollow, and ultimately to the Union Church of Pocantico Hills. Once, on a trip to MOMA together, Robin took me to see a Chagall painting that had been influential to her. More than that, she loved Chagall’s work, the non-representational colors, and the whimsical imagery blended with figurative art. So, I thought it would be a treat to see the Chagall windows at Union Church, which I had also never seen. Then we would go to Blue Hill Stone Barns for dinner, stay the night in the area, and make our way back to Staatsburg. What Robin also didn’t know was that I packed my mother’s wedding ring for the trip.

Upon arrival in Columbus, we went to see the International at the mechanic’s shop. It was the first time I had seen the R-110 in about ten years, but I knew upon first glance that Ole Smokey was not up to be driven in the July 4th parade. I abandoned that plan immediately. I asked if they could get the truck roadworthy in three more days, as I still hoped to drive the pick-up back to New York with Robin. They said that they could, and so after the festivities, we set out east, once again on Highway 40 from fifteen years before.

Nothing went according to plan. The steering seemed even looser than I had remembered, and the truck lurched right or left after the slightest bump. The engine was knocking a bit and the exhaust seemed to be channeled directly into the cab. Robin held her head out the door window like a puppy. We made it to Zanesville and then to Cambridge, but then Highway 40 merges with Interstate 70 before it deviates in Wheeling, West Virginia, where we made our way into Pennsylvania to around Washington, about 30 miles south of Pittsburgh. And there, at a truck stop, where we pulled off to refuel, we wouldn’t go further. After filling the tank, I started the R-110 up and threw a rod instantly. There was no quick fix to catastrophic engine failure, and what I thought would be a romantic journey was turning bleak.

I called my insurance company, and they were willing to load the pick-up on a flat bed and tow her—and us—back to the Hudson Valley. But the driver wouldn’t arrive until morning, so we dined on T-bones, mashed potatoes and whiskey that night before heading to a nearby hotel for a rough night’s sleep under a chintz bedspread.

We left the next morning. Ole Smokey was strapped to the top of the flat bed, the driver, Robin and I were three-across in the front seat, and we had an eight-hour drive ahead of us. Gone was the bucolic Pennsylvania farmland that I planned to drive by. Gone were the little inns where I had planned to stay on the three-day journey. Gone was the triumphant crossing of the Hudson from Nyak to Tarrytown. Gone was Union Church and the Chagall windows. Gone was dinner at Blue Hill at Stone Barns. Gone was the entire, romantic road trip—at the end of which—I had planned to propose.

Robin was a good sport about it all, and I think we treated ourselves to a nice dinner out when we got back that Saturday, but then I had an idea. I was already in contract on the farm, so I called the real estate agent to see if we could get permission to go walk around on Sunday morning. There hadn’t been anyone living there for several years, but I didn’t want to trespass.

“Hold On,” Mule Variations, Tom Waits, 1999

Before us, the farm had only been hayed for several decades, and the fields had just been cut that July. The round bales lined the perimeter of the tree line and the field. We parked by the house, because there wasn’t a road to the barn at that time. And then we walked the length of the field and back up to where there is a path through the hedges to a small field that connects the 7-acre field by the barn to the 15-acre field along Milan Hollow Road. The path was overgrown and covered with poison ivy, but we made our way to an ancient oak tree at the end of the path. This tree is visible in arial photos from 1936, so it must be over a hundred years old.

And that’s where I told Robin that I wanted my future to be on this farm and I asked her if she could see herself rooted in such a place. By no means was the answer to this question a foregone conclusion. I knew Robin craved adventure and travel; exploration and new experiences were part of her DNA. Would she want to settle down? I really don’t remember what her answer was, but it wasn’t “yes.”

I confessed to Robin what I had planned for our road trip in the Binder, the backroads, country inns, the Chagall windows and dinner at Blue Hill at Stone Barns. Then we decided we should just go to Blue Hill anyway. They didn’t take reservations for Sunday lunch, so I figured if we drove down to arrive early enough, we might get in. And we did, the last two seats at the bar! We ordered a bottle of Domaine de Montbourgeau Crémant du Jura Brut Zero and settled into our lunch. We talked about the failed road trip and laughed at the Truckstop T-bone steaks. And, in classic Blue Hill hospitality, the staff recognized that we were having a great time and in love. They offered wine pairings for the courses and then invited us into the old manure room at Stone Barns for one of the main courses. And that’s where I proposed with my mother’s ring, in an old shit house used by farmers long ago. But there wasn’t an immediate “yes.”

After lunch, we walked the grounds at Stone Barns and talked about the animals and the farm and how inspirational the place was. Then we drove back to Robin’s apartment on the Upper West Side, and on a whim, went to Central Park to stand in line to see if we might get into Shakespeare in the Park. We didn’t have tickets—and it wasn’t even Shakespeare in the Park that night but the Public Theater Public Works production—however seats were given out immediately before showtime for no-shows at the box office. We hadn’t lined up early, and the queue ahead of us seemed longer than there could be seats available, but we waited and sidled along as people in front of us received their tickets and proceeded inside. There was a group of four ahead of us, but there were only two tickets left. As they debated how to split four tickets, Robin blurted out to the usher: “We just got engaged!” And just like that, I knew the farm was more than a dream and—most importantly—I had a partner in the journey. The tickets were handed over, and we ended that magical day with great seats in the Delacorte to see The Tempest.

The International R-110 was ultimately restored in Pine Plains and is now at Branchwater awaiting a new fuel tank. Robin and I married under the oak tree behind the barn the following October. And, at least for me, I didn’t fully grasp the scope of the farming project we were about to undertake. What lay ahead was a lot like getting that red pick-up truck from Iowa to Ohio and from Ohio to the Hudson Valley: delays, breakdowns, repairs, catastrophic failures, pivots, adjustments, more delays, limited successes, shifting gears, reconsiderations, doubt, a little luck, and optimism—always optimism. That’s farming, but that’s also life.

The day we bought the farm - Jan, 2014

what we’ve been up to lately

We recently had visits from our New York and Connecticut distributors. The Vintus NY and Missing Link teams came up for farm tours and tastings. It’s always valuable to spend time with our partners!

what we’ve been mixing up lately

With the onset of fall, we turn to the darker side — of spirits! The base of this month’s featured cocktail is our barrel-aged apple brandy. We consider our apple brandy to be a bridge connecting our fruit eaux de vie with our barrel-aged grain whiskeys. A best of both worlds scenario!

Apple brandy, fresh lime and a sage-infused simple syrup - take our Sage Advice and add some warmth to these cooler fall evenings.

Sage Advice

2oz Branchwater Apple Brandy

0.75oz Fresh Lime Juice

0.75oz Sage Simple Syrup*

Combine with ice, shake and strain into chilled coupe. Garnish with a sage sprig

*combine equal parts sugar and water (1 cup), heat on low. When sugar is dissolved, remove from heat, add 8 leaves of sage and steep for 45 min-1 hr. Refrigerate unused syrup for up to 3 weeks.

Looking ahead…

Knit & Sip - On the eve of the Rhinebeck Sheep & Wool Festival, gather with friends and fellow fiber enthusiasts to relax, create, sip and snack - all against a backdrop of natural beauty. Sit around the fire pit while savoring a craft cocktail made from spirits grown in the surrounding fields. Enjoy one of our specialty food boards while watching our flock of ducks take their evening stroll. Shop our farm store and stock up on provisions and gifts from local farms and artisans. Explore the farm at your leisure, drawing inspiration for your next creative project from the colors of the season. Knit & Sip at Branchwater Farms will run from 4-7pm on Friday, October 17th. Information and tickets here

Navy Strength Gin Release Party - Please join us for our latest spirit release - Branchwater Navy Strength Gin! For those of you new to the term, it originated in the 18th century when the British Royal Navy required its spirits to be of a certain strength to ensure they would still ignite gunpowder in case of a spill. Turns out that’s around 57%. We find our Navy Strength Gin adds a little more heft and makes for a great cooler weather version of a Negroni, Martini or Bijou.

As with all of our release parties, we will be joined by other makers in a collaborative event that highlights the abundance of this valley! Brian Spaeth will pour an exciting lineup of spirits from Tenmile Distillery, Mimi Beaven (of former Made in Ghent fame) will be here with her irresistible jams and baked goods, and Maria Clarke will have some of her ceramic treasures available for purchase as well. Please come out and support local artisans and have a lot of fun while doing so! Saturday, November 8th (12-3pm)

Branchwater Holiday Craft Fair - We’re back for our 4th annual holiday craft fair! Give hand-made, thoughtful gifts for the holiday season and support local artisans in the process. Enjoy a hot dog and craft cocktail while you’re at it! Saturday, December 6th (12-3pm)